How I Wish I’d Said Goodbye to My Dog

Updated on March 12, 2024

Looking back, I wish I’d said goodbye to my dog in a different way. I love the W.R. Purche quote, “Everyone thinks they have the best dog. And none of them are wrong.”

But I’m here to tell you that in the hierarchy of best dogs, my first dog, Yuki, was right at the top.

She was loving, loyal, eager to learn… and she packed more life into her seven years than some adult humans have in their entire lives. And that makes it seem all the more unfair that she got only seven years with us.

Well, let me rephrase. It’s probably more accurate to say that my husband and I got only seven years with her before a sudden illness forced us to make the hardest phone call of our lives, scheduling her final appointment at the vet.

Saying goodbye to Yuki (my first dog) didn’t just leave me devastated and sad — I was also frightened and overwhelmed, and in retrospect, I realize I was also fairly clueless about what to expect or what I could do to make the day less frightening for my beloved pup. Since then, I’ve learned an abundance of valuable lessons on how to make a pet’s last day with us a better celebration of that animal’s life.

With that in mind, here are a few things I did right — and a number of things I wish I’d done on Yuki’s last day with us.

Things I Recommend Pet Parents Do

Take the time to memorize everything. That last morning, I held my sweet girl close, but I also made a point to step back and look at her — really look at her — to make sure I’d always remember the little things that stood out about her. I noted the asymmetry of the white spot on her chest and the hint of brown in her otherwise black coat. Three of her paws had bits of white on the toes, but one was all black. I won’t forget that, ever.

Make decisions ahead of time when possible. My husband and I decided before we even got into the car that we’d have her privately cremated and keep her remains with us. Not because we had a plan for what to do with them (and, in fact, eight years later, they’re still in the closet), but because we knew we weren’t ready to let go. I’m glad we didn’t waste time during those last moments trying to figure out the right choice for our family.

Spoil the heck out of her. By the time we knew it was time to say goodbye to Yuki, she had reached a point where it was important that we do it quickly for her sake — we couldn’t bear to see her suffer. But even though she was struggling, she still enjoyed food, and I wish we’d thought to pick her up a burger or a pint of vanilla ice cream on the way to the vet (or asked a friend to bring it to us). If nothing else, I wish we’d brought a bag of her favorite treats to try to distract her from what was going on. This is something I’ve done for friends saying goodbye to their own chow hounds, and it not only spoils the dog in a way he’s likely not accustomed to (which, at the very least, might take his mind off of his pain or anxiety he feels at the vet), but it can also add a bit of levity. Watching my friend’s dog, Floyd, lap up his ice cream, sending splashes across the room, made us both laugh on a day that was all too full of tears. With our cat, Meeko, we gave her as much of her favorite wet food as she wanted on her last day.

Mark the moment in a peaceful way. My friend and colleague, Dr. Jessica Vogelsang, works in pet hospice and home euthanasia, and one of her recommendations is to light a candle during the appointment, and then, once the pet has passed and you’ve said your final goodbye, blow it out to symbolize the end. This can be accompanied by a prayer or saying, or simply a kiss on the top of your pet’s head. We stayed with Yuki for quite a while after she’d passed — and that was fine — but we didn’t really have a way to mark the moment ending. I think that would’ve made it easier to leave. How can you ever feel “done” in that situation, you know?

Consider a home euthanasia. This didn’t even cross my mind at the time, but think about it. Where is your pet more comfortable: at home or the vet’s office? Yuki actually loved our vet (and the feeling was mutual), but there’s no doubt in my mind that going into that office was more stressful for her than the same procedure would’ve been in her doggy bed at home. And now, with more perspective, reducing the stress of the day for Yuki should’ve been my top priority.

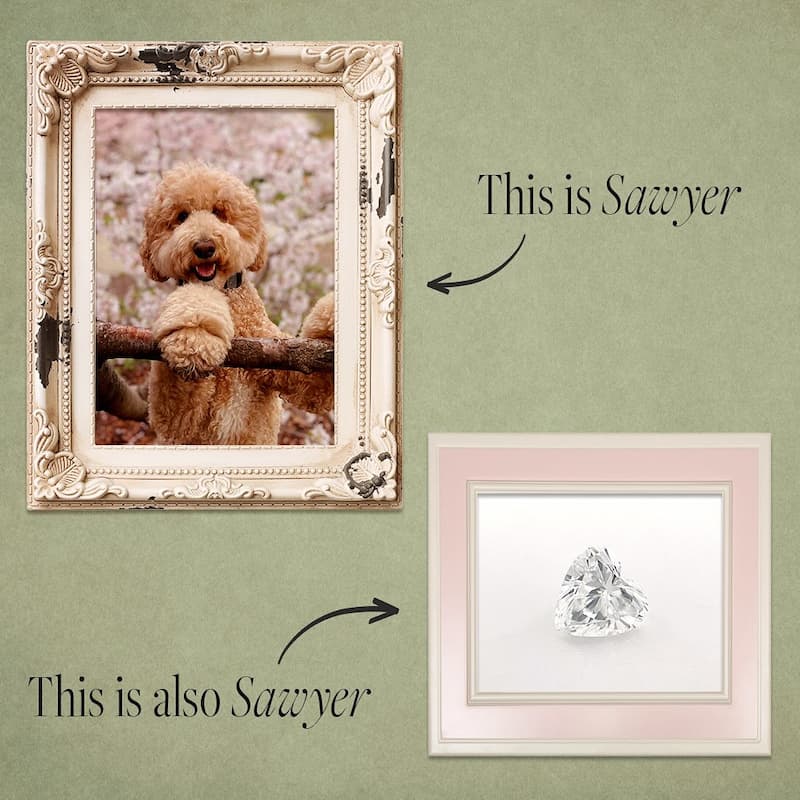

Ask the vet for nose and/or paw prints. Oh, I could kick myself for not thinking to do this. There are so many beautiful ways to memorialize your pet through jewelry or art.

All featured products are chosen at the discretion of the Vetstreet editorial team and do not reflect a direct endorsement by the author. However, Vetstreet may make a small affiliate commission if you click through and make a purchase.

One way to memorialize your pet is with a piece of diamond jewelry from Eterneva. Your dog is a once-in-a-lifetime pet, and you can keep a piece of them with you at all times. You receive a kit from Eterneva and send them either some of your dog’s hair or some of their ashes from cremation.

Using a careful process of heat and pressure, infusing your pet’s hair or ashes produces a one-of-a-kind diamond. Your beloved pet will always be by your side whether you choose a ring, necklace, or something else from Eterneva.

Take more pictures. Taking pictures on that day isn’t right for every situation. Because Yuki truly wasn’t well and really wasn’t herself, it wouldn’t have been right for us. But I wish I’d taken more pictures of our everyday life with Yuki in general (easier to do now that we all have smartphones), and I’ve seen some really beautiful photo shoots commemorating the day a dog goes to heaven. So I do think it’s something to consider if you’re not in an emergency situation.

Lastly, be sure to show yourself kindness as you grieve. Many of us feel the loss of a pet in a truly profound way — sometimes we feel it even more deeply than the loss of a human loved one. Surround yourself with people who understand (and don’t judge) your grief, allow yourself time to heal, and trust that one day, the pain will cease. You’ll even be able to talk about your pet without tearing up — I swear! Although you might find the tears still flow on occasion (like when you’re remembering your last day together, for example). And that’s OK, too.

More on Vetstreet: